Emma:

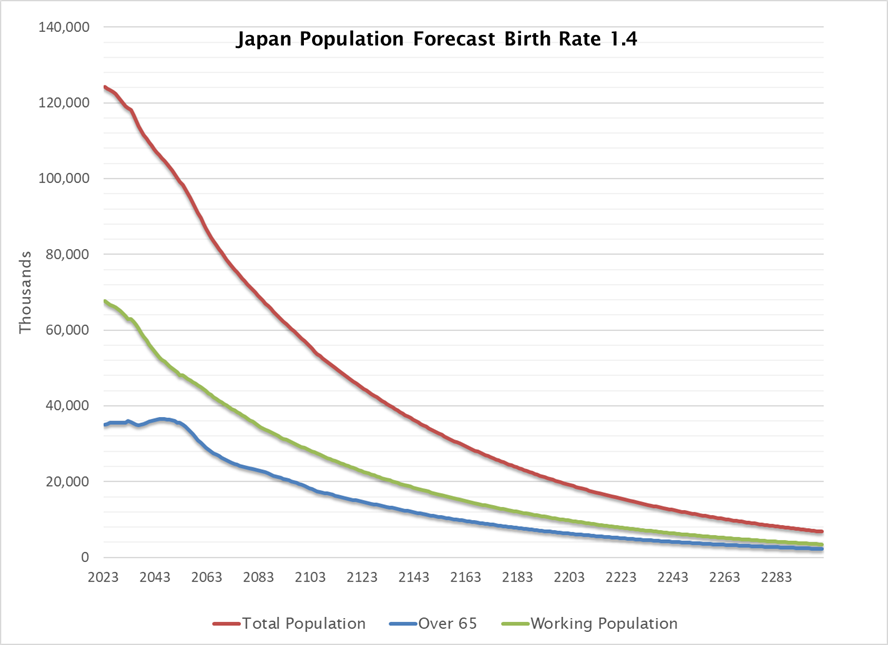

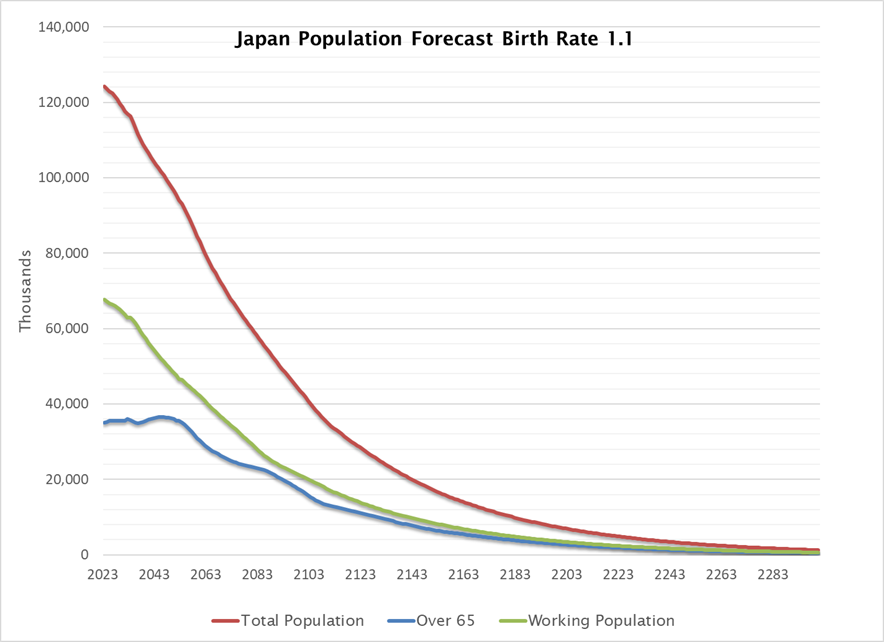

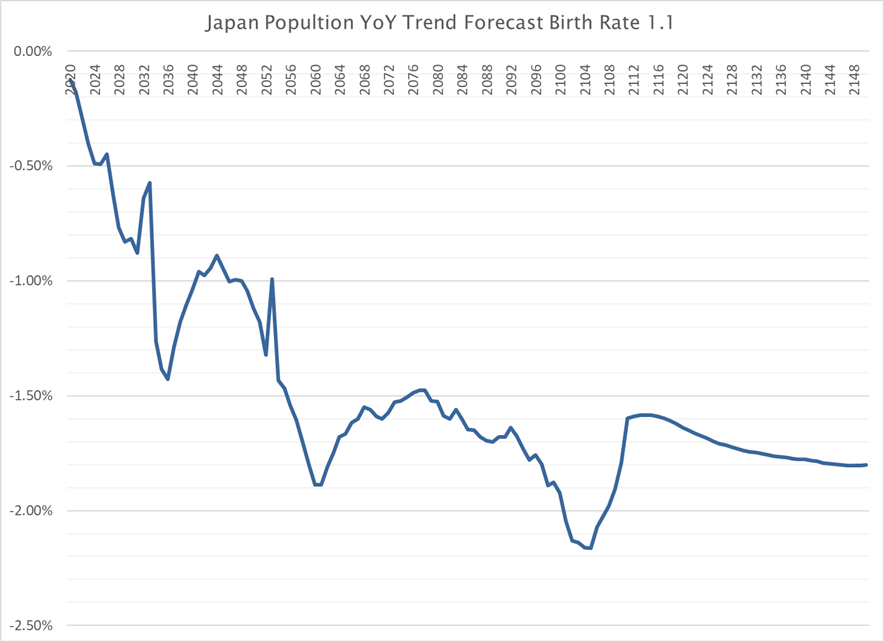

John, let me start with a broad question that’s been on my mind lately: How do you think Japan’s demographic trajectory—particularly this consistent downward trend in population—fits into the broader narrative of global economic shifts? We talk often about Japan being an early example of an aging society, but these forecasts (under birth rates of 1.1, 1.25, and 1.4) indicate it’s not just aging. It’s shrinking at a faster clip than many might have initially expected.

John:

John:

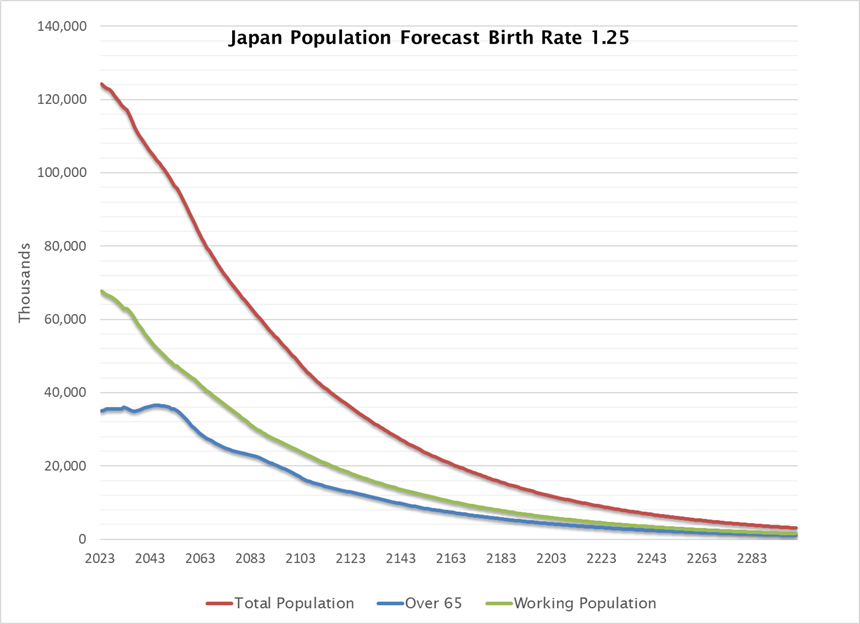

That’s a great question, Emma. For a long time, Japan’s demographic changes were often discussed as if they were somewhat isolated—unique to Japan’s social and cultural context. But now, with many developed nations starting to see aging populations and below-replacement fertility rates, Japan’s situation looks more like a leading indicator for global trends. This 1.25 scenario you just showed underscores how the country’s working-age population (in green) is shrinking significantly, while the total population (red) remains on a steady downward slope.

It’s worth remembering that Japan has been here before in a different sense: if you look at its economic history since the late 1800s, there was a time when rapid population growth fueled a transformation from an agrarian society into an industrial powerhouse. World War II and its aftermath then saw a demographic rebound that, in many ways, helped power the “economic miracle.” Now, those forces have reversed. Where once Japan drew its economic strength from a growing workforce, it now faces the headwinds of that workforce shrinking.

Emma:

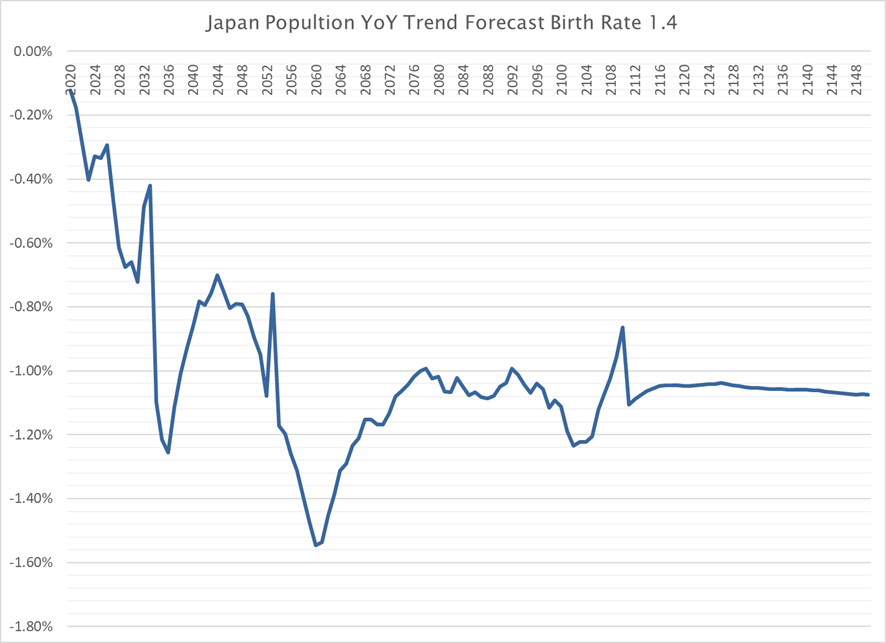

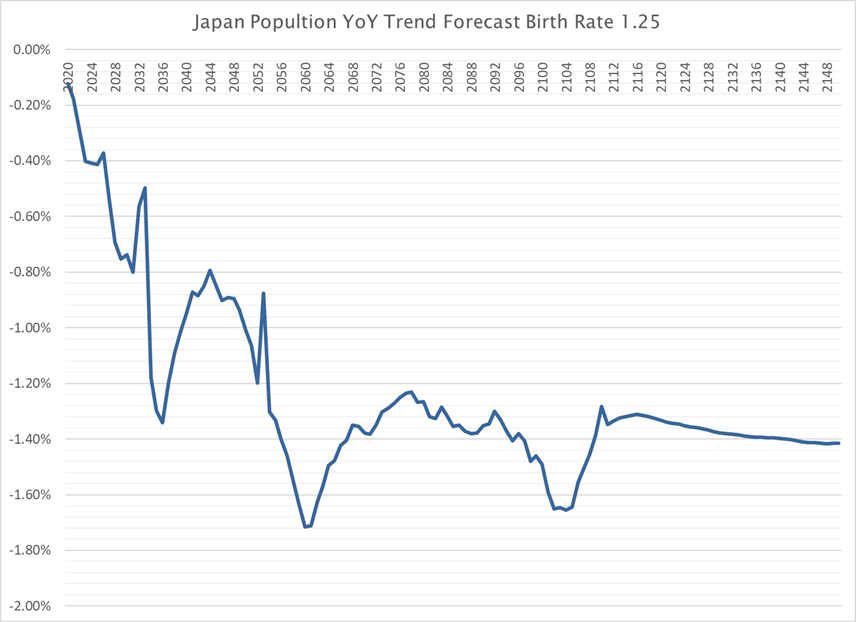

And shrinking at a fairly steady rate, if we look at the year-over-year percentage change charts. Even if we assume a birth rate of 1.4, we’re still looking at a net decline. That’s the surprising thing: whether it’s 1.1, 1.25, or 1.4, the endgame is a smaller Japan over the coming century, just at different speeds.

John:

John:

Precisely. And there’s a key economic concept here: long-term GDP growth is typically driven by the sum of labor force growth and productivity growth. If the labor force component goes negative, then productivity has to significantly outperform just to keep the economy from contracting. That’s no easy feat. Japan is famous for its robotics and manufacturing prowess, but even that may not fully offset the scale of the demographic decline.

On the demand side, a smaller population means a smaller domestic consumer base. Businesses that rely on selling to a broad swath of Japanese consumers—think retail, local services, and real estate development—could struggle with consistent revenue growth. Meanwhile, certain sectors, like healthcare, elder care, and advanced robotics for assisted living, might find new opportunities.

Emma:

This interplay between a tighter labor market—leading to potential wage growth—and a shrinking consumer base—leading to lower overall demand—is fascinating. Some argue that labor shortages will push wages higher and spark inflation. But if people are also exiting the market as consumers, any inflation might be capped by the reduced ability of companies to pass on higher costs.

John:

Right, and that tension is why Japan has seen persistent low inflation or deflation for decades. The Bank of Japan has tried various forms of monetary easing, even negative interest rates, hoping to stimulate both wage and price growth. However, when the fundamental demand base is shrinking, the results are muted. The 1.4 scenario is a bit less severe, but still, you see the population dropping. There’s a sense that these structural forces overshadow short-term policy measures.

It also circles back to government finances. Japan’s public debt-to-GDP ratio is exceptionally high. In a shrinking economy, the tax base is squeezed, making it more challenging to fund social security, healthcare, and pension obligations. Low interest rates have helped the government service this debt relatively cheaply. But with fewer workers, the sustainability of that debt remains a question.

Emma:

Exactly, and let me bring up the 1.1 scenario because that’s where the picture looks most dramatic. In that forecast, the population fall is steeper, and the workforce decline happens faster. For instance, the total population might end up halving in a relatively short timeframe compared to historical standards.

John: Yes, the 1.1 scenario makes you question how Japan will handle healthcare, pension, and elder care costs with so few younger workers. One possibility is that robotics and AI become integral to elderly care, which could boost productivity in that sector. Another is that Japan might, out of necessity, reconsider immigration policies. Immigration has historically been low, but faced with an existential labor shortage, policies might shift to allow more workers from abroad.

Of course, that would require broader cultural and social acceptance, which is complex. But countries like Germany have used immigration to offset some of their demographic pressures. Whether Japan goes that route in a major way remains to be seen.

Emma:

And on the flip side, some economists suggest that a truly advanced economy can shrink in population yet still maintain a decent standard of living if productivity outpaces the population loss. Think about technology’s role: telemedicine, remote work, advanced automation in factories—these could revolutionize how an economy functions even with fewer human workers.

The problem is, these leaps in productivity usually take time to diffuse throughout society. Japan’s demographic decline isn’t waiting around. It’s steady and, by some measures, accelerating. So the key question is whether productivity can ramp up fast enough.

John:

When we consider investing in Japan, we also have to factor in the cultural dimension. Japanese households are known for high savings rates, and the elderly demographic often parks money in relatively safe assets like government bonds. As that demographic eventually draws down savings, we could see shifts in the bond market. Will interest rates rise if there’s less domestic demand for government debt? Or will institutional buyers, like the Bank of Japan and pension funds, keep purchasing?

That’s also tied to the potential for inflation. If the government needs to finance deficits and fewer domestic savers are around, could that force monetary authorities to create more money, risking an uptick in inflation? It’s a delicate balance, and quite unprecedented on this scale.

Emma:

One element we shouldn’t overlook is Japan’s global economic role. Even though the domestic population may shrink, Japanese multinational corporations have extensive overseas operations. Companies like Toyota, Sony, and SoftBank are global players. So while the domestic workforce contracts, these firms might continue growing abroad, which can still feed back some level of revenue into Japan.

However, that doesn’t completely solve the internal issues around pension funding, healthcare, or real estate oversupply. Rural Japan is already seeing abandoned homes (akiya) because of the population exodus. Urban areas might stay more vibrant, but rural and suburban regions could face steep declines in property values.

John:

That’s right. Urbanization might intensify, with Tokyo, Osaka, and a handful of major cities staying relatively populated, but rural areas hollowing out rapidly. For investors interested in Japanese real estate, this is a big consideration: certain local markets might become essentially unviable, while centrally located properties in major cities remain stable or even gain value over time.

And beyond real estate, we should think about technology adoption in daily life. For instance, the push towards a cashless society in Japan has been slower compared to some other Asian countries, largely due to an older population preferring traditional cash. But as new generations come along, even if smaller in number, they might accelerate digital adoption, changing the consumer landscape.

Emma:

Right. And speaking of consumer landscape, there’s also the notion that as people get older, their spending patterns change. Healthcare, leisure, and certain types of premium goods might do well. More “youth-centric” sectors could find fewer customers. On top of that, with less pressure to buy large family homes, the housing market might shift towards smaller, more efficient spaces designed for singles or couples without children.

Let’s not forget how all of this ties back to monetary policy. The Bank of Japan has long aimed for a 2% inflation target, but demographic pressures have made that a perpetual challenge. Even if wages rise in certain areas, the overall consumption base is narrowing. That’s why we might keep seeing ultra-low interest rates, perhaps even for decades.

John:

And we have to remember Japan’s role as a major creditor to the world. Japanese investors hold a substantial amount of foreign assets. If demographic pressures lead them to repatriate some funds—say, for retirement needs—that could affect global bond and equity markets. On the other hand, if Japan’s economy struggles to provide attractive yields at home, Japanese capital might keep flowing outward. It’s a big question mark for global capital flows.

But Emma, one aspect that often gets overlooked is how older populations vote and shape policy. As the electorate skews older, there may be resistance to certain reforms—like pension overhauls—because they directly affect that large voting bloc. This complicates the political willingness to address issues like immigration or reorienting fiscal priorities.

Emma:

Exactly. It’s a demographic feedback loop. An older electorate has less incentive to implement radical changes that might only bear fruit decades later. That hesitancy can lock in certain policies—even if they’re unsustainable. And while small adjustments to the pension system have been made over time, truly bold moves remain politically sensitive.

Another angle is the relationship between corporations and lifetime employment—a traditional hallmark of Japan’s labor market. As the working-age population shrinks, companies might cling more tightly to existing employees, further limiting labor market dynamism. Or they might need to become more flexible, offering part-time or remote work, especially if they can’t fill all positions with domestic talent.

John:

Let’s consider the global lessons here. Other countries watching Japan might think, “This could be us in 20 or 30 years.” So Japan becomes a test bed. If it finds innovative ways to maintain living standards or growth despite a shrinking base, that model could be replicated elsewhere. But if it struggles significantly, that might signal to other countries to accelerate their own policy changes—like encouraging higher birth rates or more immigration sooner rather than later.

Emma:

That’s what makes it so critical for us, as portfolio managers, to watch Japan closely. Not just because it’s a top-three global economy, but because the strategies it deploys might shape how we think about future investments in other aging nations. Should they double down on robotics? Will they open up to immigration more than we expect? Will they shift tax policy to encourage higher fertility? All these variables matter.

From an investment standpoint, companies that cater to an aging population—healthcare providers, pharmaceutical companies, robotics for elderly care—could see stable or growing demand. Meanwhile, consumer sectors relying on young families might face prolonged stagnation. Also, the macro environment might remain one of low yields and persistent attempts to spark inflation, which influences bond and equity strategies.

John:

Exactly. And one final point: with the population decline, there’s a rethinking of economic frameworks that were designed in the early to mid-1900s, an era of growth. For instance, Keynesian demand management presumes some baseline population expansion or stability. In a shrinking scenario, the interplay of government spending, taxes, and debt looks different. Pension systems, built when there were many working-age people for each retiree, have to be overhauled. Monetary policy, aimed at cyclical demand stimulation, hits structural demographic roadblocks.

That’s why we see talk about “post-growth” models, where quality of life, technology integration, and environmental sustainability might take priority over raw GDP expansion. Japan could lead that conversation, simply because it’s so far along the curve of demographic change.

Emma:

Which means the entire global community has a stake in seeing how Japan manages this transition. If Japan successfully pivots and finds a sustainable model, it could ease concerns about other countries facing similar patterns. If not, the pressures might increase globally, especially as more societies tip into negative population growth.

John, thanks for this deep dive. It’s fascinating to see how these population forecasts—1.1, 1.25, and 1.4—affect everything from inflation expectations to public debt management to real estate markets. We’ll definitely keep these charts on our radar and see if the birth rate budges or if policy shifts significantly.

John:

My pleasure, Emma. Always a stimulating discussion. Let’s be sure to revisit these forecasts in a year or two to see if reality aligns with them, or if there are any surprising policy moves. Until then, these charts offer a valuable roadmap for thinking about where Japan’s economy might head, and how we, as investors, can position ourselves.

Online References:

Population Statistics|National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

File | Browse Statistics | Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/populate/dl/01.pdf

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Handbook of Health and Welfare Statistics

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research